Nachleben. Every Image Is a Potential Painting

- Location:

- Exhibition Hall B

- Artists:

- Ignasi Aballí, Marina Abramović, José Manuel Broto, Jean-Marc Bustamante, Toni Catany, Carlos Correia, Gil Heitor Cortesão, Pierre Gonnord, Susy Gómez, Miki Leal, Rita Magalhães, Tracey Moffatt…

- Curatorship:

- Es Baluard Museu

“Every Image Is a Potential Painting” takes the form of the second part of “Nachleben: Painting as Conceptual Art” and aims to answer a series of questions: Why is painting potentially the most conceptual of all existing art forms? Why can any image be a painting? Why is the emergence of abstraction for many the most decisive event in art during the 20th century? And why do we still talk about painting? Probably because the different moments in painting’s history always imply a new definition, and we have known for some time that the only thing set in stone is the word ‘painting’ itself, extended and bent without breaking, like a fishing rod, in order to assimilate an endless number of meanings. Hence the polyhedral character of painting, capable of having multiple faces, but also the need to ask ourselves the same question again and again: What do we call painting today?

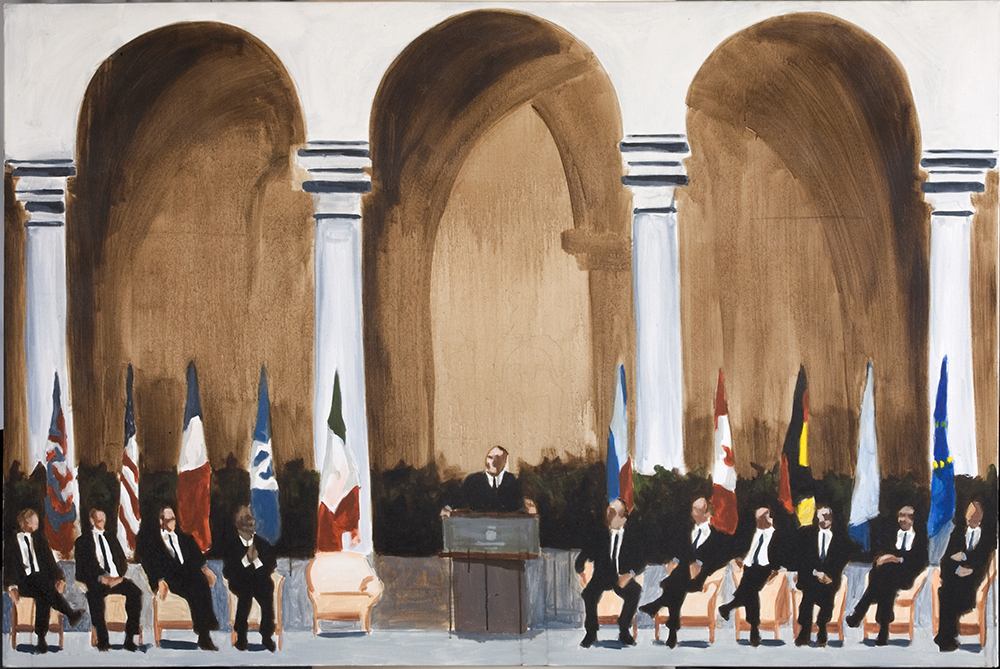

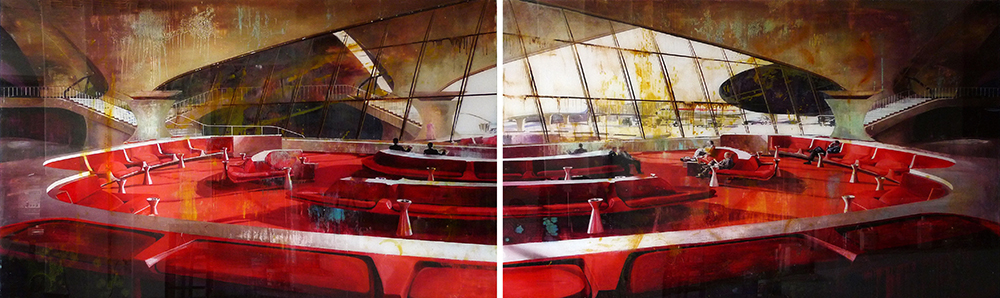

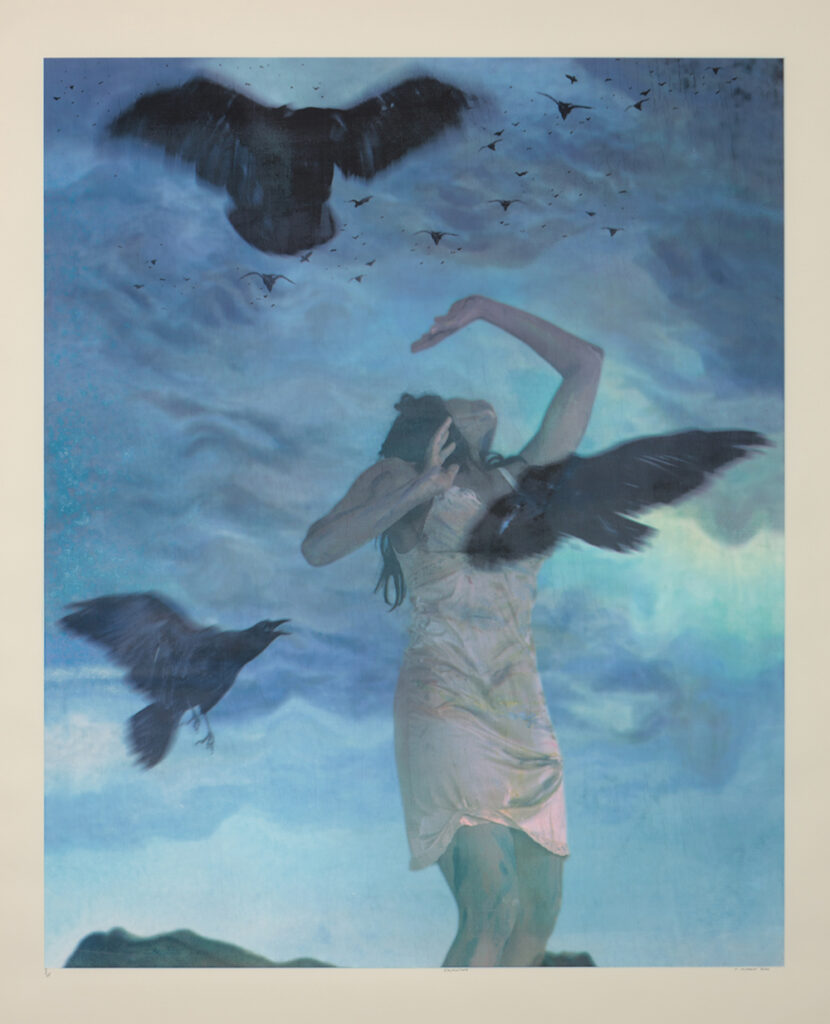

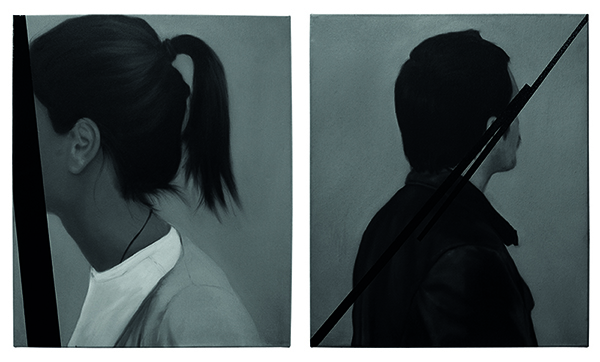

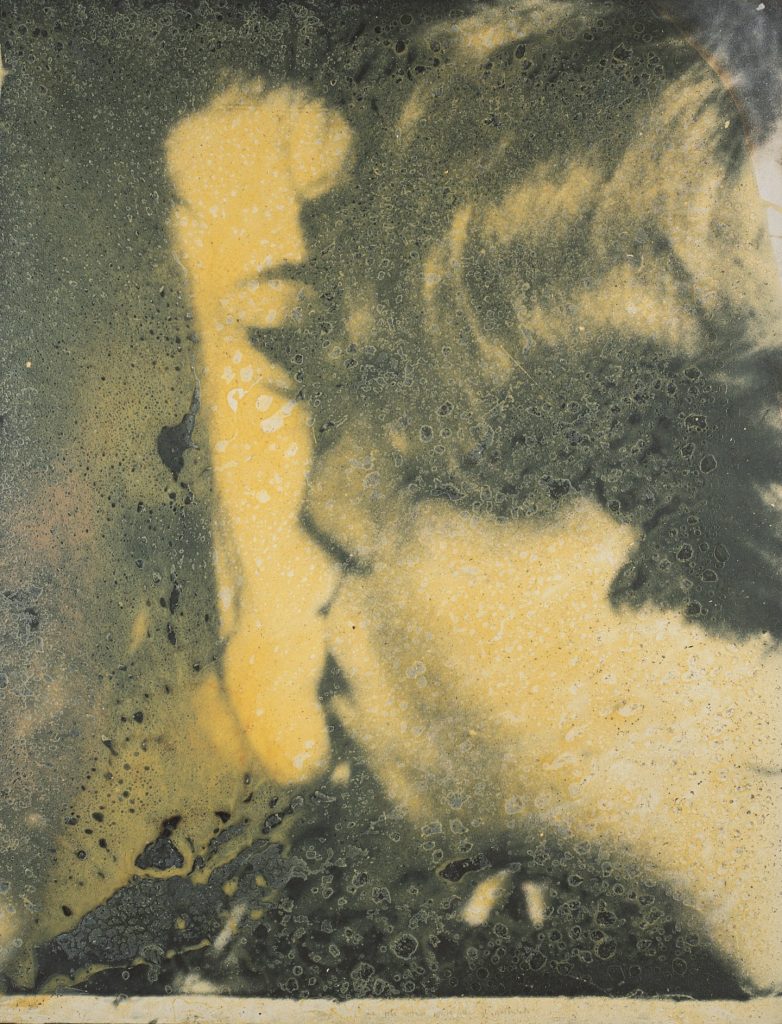

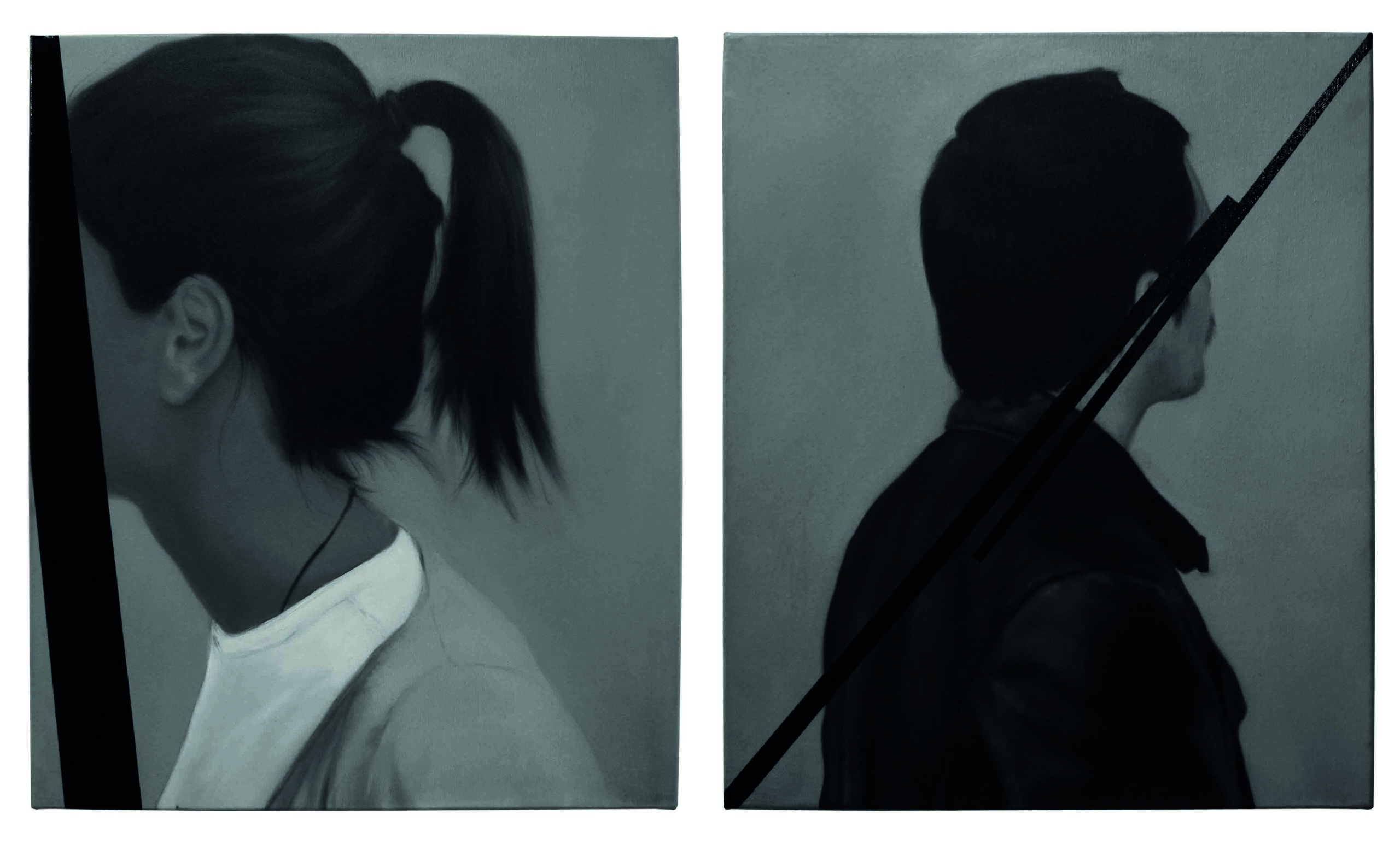

The most widespread painting trend outside painting is, precisely, photography’s appropriation of its mannerisms, by recovering and combining the structural and rhythmic tradition of the history of painting, be it in the symbolism and combination of colours, in the exportation of patterns and figures or in the paths of light and its most pronounced shadows. Let us think, among other examples, of the photography of Toni Catany, Pierre Gonnord, Marina Abramović, Tracey Moffatt, Darío Villalba or, Susy Gómez, who used photography to approach painting as an idea and a concept. Therefore, painting has also managed to migrate from one body to another, embracing other materials and processes in order to reincarnate through other mediums. This is something that should not surprise us if we think about how, despite the passing of time, the tendency we have to see the world in pictorial terms is still prevalent. Because before each image we project an unconscious expectation that is nothing more than the fruit of an irreversible contamination of visual references that we have acquired previously, for example, when watching classic films that have been inspired by paintings from other periods. In this sense, photography was the first outside medium that was able to make the meaning of traditional genres more kaleidoscopic, operating a sort of trompe l’oeil on what had always been considered painting. The pictorial frame managed to extrapolate itself to the video frame. The lights, the colours, the density of the grain, the themes, the framing and the compositions all draw on the history of painting.

In Perejaume’s Pintura-Fuirosos (1990), we can see how painting is understood as an intellectualised act. For him, painting became an intellectual art, capable of rising out of the earth as something human, with the need to expand in order to occupy a space that previously seemed not to belong to him. The medium is not as important as the plasticity that the medium allows when it comes to a reassignment of meanings. All this can be extrapolated to Ignasi Aballí’s intention to explore other possibilities for painting which cannot be considered painting in the strict sense.

Far from signalling the end of painting and beyond its condition as a support for the pictorial in this idea of painting outside of painting, photography opened up a new path once one of modernism’s greatest fears was overcome: the fear of fabrication. Nowadays there is a special way of seeing and representing that has led many artists such as Alain Urrutia, Andrei Roiter, Carlos Correia, Tomás Pizá, Miki Leal to adopt some of its characteristics, visible in their rough way of illustrating and use of photographic and filmic sources, balancing out the ambiguous and the literal.

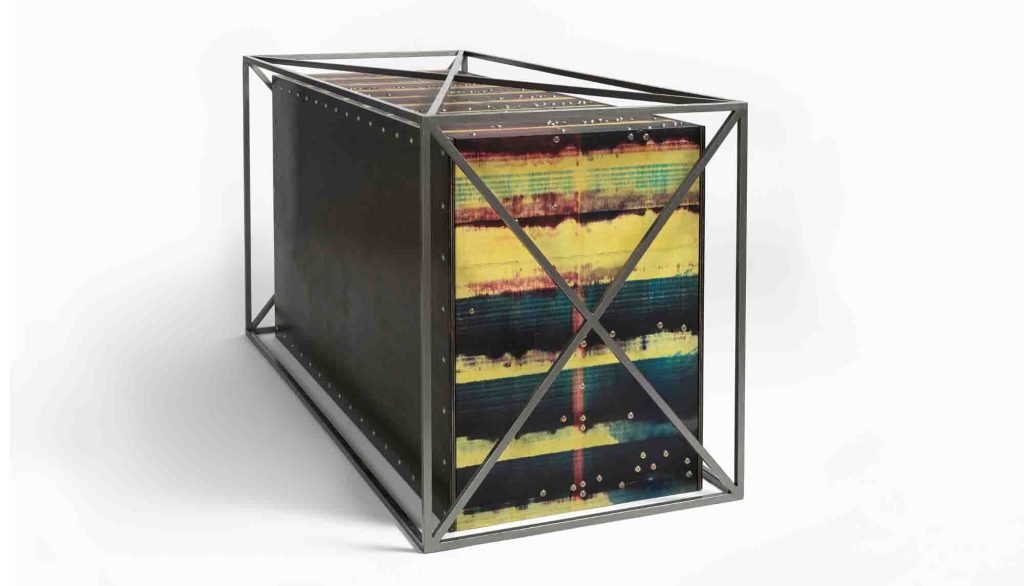

So do the paintings of Simeón Saiz Ruiz, who does not begin with photographs of reality, but with the impossible photography of media such as television; first he photographs the television and then the resulting image is photographed again several times to then be transferred to the canvas with precision, reproducing each pixel with its exact chromatic value. Concrete things seem to unravel into an abstract tapestry, but the memory of violence remains intact. In this reactivation of painting without fear of the hand being a mark of the artist, even when photography and other media are used as the starting point, an interesting way of constructing experience is concealed, of connecting reality, be it through political or historical events, everyday environments, scenes or banal objects, with historical experience and individual emotion, giving the images a category that transits between the external and the internal, the objective and the subjective. We could also talk about the fictional worlds of Tracey Moffat or Rita Magalhaes. Or the process of abstraction employed by Jean-Marc Bustamante, who in Panorama (Pink Flamingos), started off with an initial drawing that he then photographed and later reproduced by means of silkscreen printing. Mounted on a transparent surface separated from the wall, the work merges with the space that supports it, creating a panorama that connects perspectives and disciplines.

Along these same lines, a type of painting has emerged in recent decades that uses images taken from the computer screen to create highly complex spaces. José Manuel Broto has also turned to new technologies to continue his research in the field of painting. Broto persisted withon an imaginary made up of loops, spirals, traces and lines that unfold in space, but once we entered the 21st century, the colours in his paintings began to display a kind of digital acidity by which the gesture and forms never cease to be slippery. An interesting case is that of Peter Zimmermann, who transforms recognisable scenes into abstract images and later transposes them onto canvas using epoxy resin mixed with oil paint. By means of stencils he determines the composition of colour, which spreads across the surface and hides the imperfections under the sheen of the paint. The paint moves spatially, proposing a narrative journey across the surface to provoke a slipping of the gaze in the absence of a centre. This artificial sensation, of a painting coming out of a digital screen, is felt from the first moment we come across Gil Heitor Cortesão’s figurative paintings, which emerge from the images rather than from a narrative structure. Hence the absence of human figures. The artist uses the surface as a medium to produce a certain uncanniness. In this sense, the choice of acrylic glass as a support and its plastic appearance is not without reason, as it emphasises this sensation of artificiality, of history without a narrative, of a suspended narrative. It is as if the support were offered as a skin, as a structure. The production process—painting from the back of the support based on a logic of layers that is the reverse of the usual painting process, in other words, where the last thing to be painted on a canvas is in this case the starting point—disorients the spectator with a clean, hygienic appearance, disguising the texture of the manual work and flattening the paint, which seems polished to the eye.